When your tragedy happens

You will be gobsmacked

You will look up “gobsmacked”

And it will be exactly how you feel–

When your tragedy happens

My tragedy happened when the love of my life

The man I just married

107 days before

Ended his life

by

jumping

in front

of

a

[REDACTED]

Yours might be smaller

But you will have one too

And the hurt will be

BIG

To be human is to be

Gobsmacked

By at least one total horror show

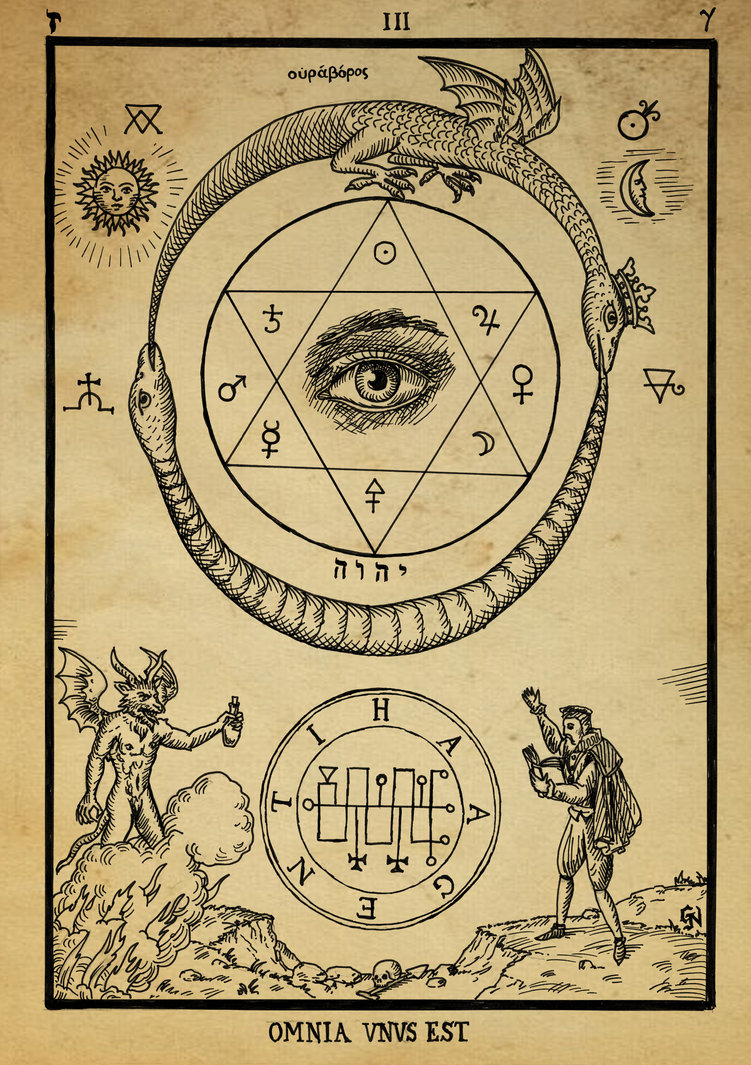

As Above, So Below: the witchiness of grief

The widowed witch is a trope. She is the archetypal, black-wearing embodiment of death and grief. Indeed, widows were specifically targeted among women during the witch hysteria that burned through Europe starting in the mid-1400s.[1] If any woman could be a witch, the widowed woman was a witch. Persecution based on these same prejudices persists in certain parts of the world today.[2]

In Lindy West’s 2019 collection of essays, The Witches Are Coming, she lays out what being a witch, or, rather, being accused of being a witch, meant in the historical context. She also explores the stigmatization of womanhood, in general, and the particular stigmatization of angry women, sexual women, loud women. Grieving women fall into this category of dangerous femininity, too. West juxtaposes what “witch” has meant in the past with the sharp irony of Trump and his henchmen abusing the term “witch hunt” to refer to any instance in which they feel unfairly targeted for what they have said or done. In her first essay in the collection, West reclaims “witch,” writing: “So fine, if you insist. This is a witch hunt. We’re witches, and we’re hunting you.” That’s fun.

And West is hardly the first to re-imagine the witch as an ultimate symbol of feminism. As a symbol of power against patriarchy and other forms of oppression. Despite that the idea is hardly new, it is a good one.

The widowed witch only highlights the terror towards the empowered feminine. The widow is cast as tainted by death and the binary opposite of the virginal and fertile young woman, who is victimized across cultures by desire rather than disdain and fear like the widow. The young widow is more terrifying still. She is a reminder that the nuclear family and marriage ideal is fallible in ways that seem somehow worse (because it is even less within our control) than divorce. The young window is terrifying because she is sexual, still, and free(-ish) from the patriarchy’s control. But at bottom, the young widow is most frightening because she is a reminder of something worse than death alone–untimely death.

The horror genre is nothing if not an homage to our collective fear of death. Often the death fear is sexualized, not just in the heaving chests of the victims but in the boogeyman itself. Recall the sexy vampires and witches that have long pervaded the page and screen.[3] Western culture sexualizes the horror of untimely and violent death and, conversely, gently romanticizes death in old age: the serenity of being surrounded by family, perfect in life, and peaceful and unafraid in dying. This should surprise exactly no one, but our culture has some serious death hang-ups. The widow as a witch, especially the young widow, is just one of many manifestations of this same shared anxiety.

And I almost understand it. Having your partner die while you are both young is a horror show. The invisible grief shroud that we as widows wear—which emanates off us like an aura that all those who know what happened, even vaguely and from their safe distance, can see—is frightening and sad.

Back when I dabbled in academia and before I became a lawyer, my master’s thesis was about the Romani identity as portrayed in media and as performed for the “gadje” or non-Roma. My work aimed to explore perceptions of “gypsiness.” The phenomenon I tried to grapple with in that research—that is, the push against prejudice and simultaneous pull towards the power and protection in being feared—has always fascinated me. My Roma father had been absent from my life, and how his absent lineage has affected my identity has always been confusing. Looking at it from the safe space of scholarship was all I could do to try to understand. But cultural perceptions of “gypsiness” and widowhood are not dissimilar–safety and stigma present as different threads in the same Gordian Knot of identity, sense of self, and how others see us.

What (if any) ownership I have over a Romani identity feels different than my identity as a widow, though. The widow identity, the dead-partner prize, feels regrettably and entirely my own.

In some ways, that makes Coven of Widows easier to write and more personal than my half-baked thesis ever was. I know that this widowhood is singularly mine and that any power to be pulled the stigmatization of the widow as the witch belongs to me. I can have “witch.” I am not stealing it or appropriating something not mine. She is me. And, sis, if you want her, she’s yours, too!

[1] See https://www.history.com/videos/history-of-witches.

[2] See https://www.reuters.com/article/us-women-widows-stigma-idUSKBN0U10PT20151218; https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kenya-widows-witches-idUSKCN0Z900Q; https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-19437130; https://deeply.thenewhumanitarian.org/womensadvancement/community/2018/04/12/branded-as-witches-stripped-of-land-tanzanias-widows-need-support,

[3] See https://tucson.com/news/local/immortality-lecture-vampires-symbolic-of-society-s-fears-anxieties/article_5dda0a8b-4877-5162-b53b-7683d262b877.html.

June 17, 2021

One.

I was married

Briefly

To a beautiful man

Who sang to me

And our big, goofy dog

All the time

But especially during

Thunderstorms

Or fireworks

So our pup, Millie,

Would not be afraid

He soothed us

He wanted peace

But he had

None.

Two.

When you tell people that your

Partner died

Suddenly

They feel a certain way

When you tell them he died by suicide

They seem to feel something different

To feel like:

You are contaminated

You are responsible

He must not have loved you

Because you could not keep him

Happy

This bothers you

Deeply

Because you worry

They are right

Three.

There is a betrayal in almost any

Death

A supreme abandonment that cannot be undone

With it comes the revelation—that you cannot count on anyone—

Not even yourself

To promise, meaningfully

Not to do the bad thing

And betray you just the same

Death carries with her

On her wretched, time-hooked back

The caustic knowing that all people

Will rend what’s left of you

Sooner or later

More violently, the closer they get.

Four.

I cannot appreciate abundance

Now

I am aware of it, tangible

As having anything

Is

Even the non-stuff of prosperity

I can look at it

Palm it, coldly and with medical disinterest

But it cannot move me

And I do not feel it

I can give it

A token

A smile

Seven days by the beach

To watch what it should do

How appreciation and gratitude should feel

But even giving

It is a bequest

The emotionless discharge

Of the already dead.

Five.

Enter

Two small and fragile cats

An approximation of the babies

We would never have

Both named for you, vaguely

In ways that most do not

Understand

We three

Quietly

And sneakily

Haunt this house

For you

A place you’ve never lived

Six.

Those cats again.

While I am loath to admit it

I sometimes

Tell them about you

Aloud and as though they are human

Or capable of really hearing

I call you their father

Sick and pathetic, I am aware

And explain to them

What we have lost

Cooing gently and with tears

Into the vacuum of their

Small feline faces

Which reflect only

Our collective

Inability

To

Understand

What any of it means

Or how losing you

In any way, but especially that way

Could have happened.